•

the Blog

Does science need statistical tests?

By Guillaume Filion, filed under

p-hacking,

dialogue,

statistics.

• 14 October 2022 •

Some time ago, my colleague John asked for help with the statistics for one of his manuscripts.

Some time ago, my colleague John asked for help with the statistics for one of his manuscripts.

“We have this situation where we knocked out a gene with CRISPR and I want to test if it affects viability. I know that you are supposed to use a non-parametric test when the sample is small, but I have heard that you can still use the t test if the variables are Gaussian. So now I am genuinely confused. Which test should I use?”

“I agree. It’s confusing. Why do you want to make a statistical test by the way?”

“Same as everyone. I want to know if the effect is significant. Plus, I’m hundred percent sure that the reviewers will ask for it.”

“I see. I will rephrase my question then. What decision do you have to make?”

“I can give you all the details of our experiments if you want, but I’m surprised. Nobody has ever asked me that before and I thought that experimental details do not really matter so much for a statistical test. So what kind of details do you need?”

“Nothing in particular. I just want to know whether you...

A tutorial on t-SNE (3)

By Guillaume Filion, filed under

series: focus on,

statistics,

data visualization,

bioinformatics.

• 22 September 2021 •

This post is the third part of a tutorial on t-SNE. The first part introduces dimensionality reduction and presents the main ideas of t-SNE. The second part introduces the notion of perplexity. The present post covers the details of the nonlinear embedding.

On the origins of t-SNE

If you are following the field of artificial intelligence, the name Geoffrey Hinton should sound familiar. As it turns out, the “Godfather of Deep Learning” is the author of both t-SNE and its ancestor SNE. This explains why t-SNE has a strong flavor of neural networks. If you already know gradient-descent and variational learning, then you should feel at home. Otherwise no worries: we will keep it relatively simple and we will take the time to explain what happens under the hood.

We have seen previously that t-SNE aims to preserve a relationship between the points, and that this relationship can be thought of as the probability of hopping from one point to the other in a random walk. The focus of this post is to explain what t-SNE does to preserve this relationship in a space of lower dimension.

The Kullback-Leibler...

A tutorial on t-SNE (1)

By Guillaume Filion, filed under

series: focus on,

statistics,

data visualization,

bioinformatics.

• 22 August 2018 •

In this tutorial, I would like to explain the basic ideas behind t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding, better known as t-SNE. There are tons of excellent material out there explaining how t-SNE works. Here, I would like to focus on why it works and what makes t-SNE special among data visualization techniques.

If you are not comfortable with formulas, you should still be able to understand this post, which is intended to be a gentle introduction to t-SNE. The next post will peek under the hood and delve into the mathematics and the technical detail.

Dimensionality reduction

One thing we all agree on is that we each have a unique personality. And yet it seems that five character traits are sufficient to sketch the psychological portrait of almost everyone. Surely, such portraits are incomplete, but they capture the most important features to describe someone.

The so-called five factor model is a prime example of dimensionality reduction. It represents diverse and complex data with a handful of numbers. The reduced personality model can be used to compare different individuals, give a quick description of someone, find compatible personalities, predict possible behaviors etc. In many...

The curse of large numbers (Big Data considered harmful)

By Guillaume Filion, filed under

statistics,

hypothesis testing,

big data,

p-values.

• 10 February 2018 •

According to the legend, King Midas got the sympathy of the Greek god Dionysus who offered to grant him a wish. Midas asked that everything he touches would turn into gold. At first very happy with his choice, he realized that he had brought on himself a curse, as his food turned into gold before he could eat it.

According to the legend, King Midas got the sympathy of the Greek god Dionysus who offered to grant him a wish. Midas asked that everything he touches would turn into gold. At first very happy with his choice, he realized that he had brought on himself a curse, as his food turned into gold before he could eat it.

This legend on the theme “be careful what you wish for” is a cautionary tale about using powers you do not understand. The only “powers” humans ever acquired were technologies, so one can think of this legend as a warning against modernization and against the fact that some things we take for granted will be lost in our desire for better lives.

In data analysis and in bioinformatics, modernization sounds like “Big Data”. And indeed, Big Data is everything we asked for. No more expensive underpowered studies! No more biased small samples! No more invalid approximations! No more p-hacking! Data is good, and more data is better. If we have too much data, we can always throw it away. So what can possibly go wrong with Big Data?

Enter the Big Data world and everything you touch turns...

One or two tails?

By Guillaume Filion, filed under

statistics,

p-hacking.

• 11 December 2016 •

Here is a discussion that I recently had with my colleague John. He approached me with the following request:

Here is a discussion that I recently had with my colleague John. He approached me with the following request:

“I sent a manuscript to Nature and it is going quite well. Actually the reviewers are rather positive, but one of them asks us to justify better why we used a one-tailed t test to find the main result. What should I write in the methods section?”

“It depends. Why did you use a one-tailed t test?”

“Well, we first tried the standard t test, but it was borderline significant. My student realized that if we used the one-tailed t test, the result was significant so we settled for this variant. We specified this clearly in the text, and I am now surprised that I have to justify it. Isn’t it just an accepted variant of the t test?”

“To be honest, I understand your confusion. The guidelines are rather ill-defined. Actually, Nature journals make it worse by requesting this information for every test, even for those that are only one-tailed like the chi-square.”

“OK, but what should I do now? For instance, how do you justify using a one-tailed t...

Did Mendel fake his results?

By Guillaume Filion, filed under

statistics,

p-hacking,

genetics,

fraud.

• 11 April 2016 •

You went to high school and you learned genetics. You heard about a certain Gregor Mendel who crossed peas and came up with the idea that there is a dominant and a recessive allele. You did not particularly like the guy because there would always be a question about peas with recessive and dominant alleles at the exam. But you grew up, became wiser and just as you started to like him, you heard from someone that he faked his data. You felt disoriented for a while, why annoy you with this stuff at school if it is wrong? But then you came to the conclusion that he just got lucky and that he was right for the wrong reasons. After all, he was just a monk on gardening duties, why would you expect him to understand anything about real science?

You went to high school and you learned genetics. You heard about a certain Gregor Mendel who crossed peas and came up with the idea that there is a dominant and a recessive allele. You did not particularly like the guy because there would always be a question about peas with recessive and dominant alleles at the exam. But you grew up, became wiser and just as you started to like him, you heard from someone that he faked his data. You felt disoriented for a while, why annoy you with this stuff at school if it is wrong? But then you came to the conclusion that he just got lucky and that he was right for the wrong reasons. After all, he was just a monk on gardening duties, why would you expect him to understand anything about real science?

Gregor Mendel

Gregor Mendel was a monk, but he was also a trained scientist. He studied assiduously for twelve years (including about seven years on physics and mathematics), to then become a teacher of physics and natural sciences at the gymnasium of Brno. He prepared his most famous experiment for two years, meticulously checking and choosing his...

Bayesian networks and causation

By Guillaume Filion, filed under

statistics,

Bayesian networks,

causes,

correlation.

• 20 June 2015 •

The first thing you learn in statistics is that “correlation does not imply causation”. As obvious as it sounds, most human mistakes fall in this category, and not only in statistics. The major difficulty with this question is that it is fairly easy to define correlation, but it is much harder to define causation, let alone quantify it. No surprise many statisticians just avoid talking about causation to stay out of the danger zone.

The first thing you learn in statistics is that “correlation does not imply causation”. As obvious as it sounds, most human mistakes fall in this category, and not only in statistics. The major difficulty with this question is that it is fairly easy to define correlation, but it is much harder to define causation, let alone quantify it. No surprise many statisticians just avoid talking about causation to stay out of the danger zone.

However, for Judea Pearl, this is not a satisfactory answer. In his book Causality: Models, Reasoning, and Inference, he expresses his opinion vividly.

I see no greater impediment to scientific progress than the prevailing practice of focusing all our mathematical resources on probabilistic and statistical inferences while leaving causal considerations to the mercy of intuition and good judgment.

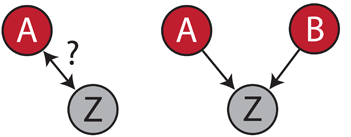

This book lays the foundation of the now popular Bayesian networks. The key idea is that you can distinguish correlation from causation if you can observe several independent causes. For instance, suppose that patients suffering from a certain type of cancer are often immunodeficient. You wonder whether immunodeficiency is a cause or a consequence of this cancer type.

Say that variable A is whether patients have...

(Mis)using the KS test for p-hacking

By Guillaume Filion, filed under

statistics,

p-hacking.

• 20 September 2014 •

A colleague of mine (let’s call him John) recently put me in a difficult situation. John is a very good immunologist who, as nearly everybody in the field, had to embrace the “omics” revolution. Spirited and curious, he has taken the time to look more closely into statistics and he now has an understanding of most popular parametric and nonparametric tests. One day, he came to me with the following situation.

“I have this gene expression data, you see... I know that a gene is up-regulated, but it is just not significant...