How to teach research?

By Guillaume Filion, filed under

motivation,

management,

leadership.

• 28 February 2016 •

One of my students once asked me how to become a better researcher. “Great question!” I thought. Instead of a straight and clear answer, I heard myself babbling, as happens when you have no idea what you are talking about. Somewhat disappointed by my non answer, I turned to my colleagues and asked how they teach research. The answer ranged from embarrassed silence to politely switching topic. Strange, I thought, it is our responsibility as principal investigators to educate the junior researchers of our group, so we’d better have some idea of what we are doing.

One of my students once asked me how to become a better researcher. “Great question!” I thought. Instead of a straight and clear answer, I heard myself babbling, as happens when you have no idea what you are talking about. Somewhat disappointed by my non answer, I turned to my colleagues and asked how they teach research. The answer ranged from embarrassed silence to politely switching topic. Strange, I thought, it is our responsibility as principal investigators to educate the junior researchers of our group, so we’d better have some idea of what we are doing.

We have a fairly good idea of how to teach skills, like mathematics, molecular biology etc. But I would argue that research is not a skill. I would argue that it is an attitude. So the real question is how to teach an attitude. There is no foolproof recipe, but here goes a subjective view that I gathered from reading, from discussions and from personal experience.

1. Motivate the change

Most students and junior scientists enter the lab with an open mind, ready to learn as many new things as possible. But most of them focus on learning technical skills (at least this is what I focused on), whereas this is the easy part of becoming a researcher. The hard part is to become a researcher.

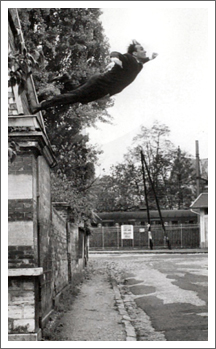

It is important to make it clear that becoming a researcher might hurt. It is an insane amount of work, a lot of frustration and a good deal of pressure. But why would anyone willingly do something hurtful? The only reason I can come up with is a certain vision of the future. The Heath brothers in the bestseller Switch suggest to ‘send a postcard from the future’. This postcard does not have to be an inspirational talk. Just talking about tomorrow is a simple way to help people project into the future. What does tomorrow look like? What is nice about it? Taking the time to have these discussions is often enough to remind us that a brighter future is lying ahead.

2. Teach the pleasure

Think of a few things that you consider yourself good at. Most likely, you also like doing them. So teaching research starts by teaching the pleasure of doing research. The good news, once again, is that most people enter a lab because they see something attractive to it. The pleasure of learning new things and working with bright minds is usually immediate. So isn’t research just pure pleasure?

Of course not. On a normal day nothing works and you understand nothing new, so research feels more like pure frustration. At some point it becomes hard to see where the pleasure actually is. As an educator, it is important to highlight that this frustration is normal. Except that it sucks big time, there is nothing fundamentally wrong with it – proof is it never goes away.

The role of the educator is to ‘give’ early successes to the students and show them that they can succeed. Early successes help build confidence, which in turn is the key to independence.

Of course not. On a normal day nothing works and you understand nothing new, so research feels more like pure frustration. At some point it becomes hard to see where the pleasure actually is. As an educator, it is important to highlight that this frustration is normal. Except that it sucks big time, there is nothing fundamentally wrong with it – proof is it never goes away.

The role of the educator is to ‘give’ early successes to the students and show them that they can succeed. Early successes help build confidence, which in turn is the key to independence.

In a celebrated psychological study, clients were given fidelity cards with stamps to collect. The card either had eight slots, or ten where two were already stamped. It turned out that clients were much more likely to complete the card with ten slots, even though they required the same amount of stamps. The upshot is that the first steps have a huge influence on the long term success of an enterprise. The educator is here to give these two free stamps to the trainees.

3. Be the example

Which is the right way to do research? Is it all about intellectual honesty? Creativity? Doing careful controls? Many things are important and there is no agreement on which of them matter the most. And even if there were, giving the list of things to do would not help. Tennis coach Timothey Gallwey realized that during the game, trainees forget what they are told to do and simply fall back into their old habits. In short, the issue is not so much what to teach as how to teach it.

A famous quote by Albert Einstein has it that “example is not another way to teach, it is the only way to teach”. I am not sure I fully agree with it, but I have to admit that I still haven’t found an exception. Teaching by example solves many issues simultaneously. First, it implicitly tells what to do. The way you do research is how it should be done. Second, it naturally ranks topics by importance. How much time, care and importance you give to a topic says how important it is. Finally, it keeps the trainee in this very particular combination of self-awareness and commitment that is favourable for growth.

This was one of the main conclusions of Timothey Gallwey. Telling trainees what to do does not help. Much more useful is to let them discover it through hints, questions and demonstrations. What are you doing different when it works? What do you notice when you are not making progress? The key is to help trainees realize that many resources are available in their own experience and in their surroundings.

Epilogue

When I sat to write this post, I thought it would be a list of important things to do in research. Things just did not go this way. The more I wrote, the more I realized what’s wrong with this idea. It’s easy to give advice, to say what’s important and what’s not. Much harder is to know how to help. This takes listening. And great mentors are above all great listeners.

« Previous Post | Next Post »

blog comments powered by Disqus