The most important quality of a scientist

By Guillaume Filion, filed under

science,

management,

opinion.

• 15 September 2020 •

When I established my lab and started to recruit people, I thought that it would be interesting to gather some information about what makes a good or a bad scientist. To this end, I designed a short questionnaire with eight questions. There was no right or wrong, nor even a preferred answer. Those were just questions to help me know the candidates better.

When I established my lab and started to recruit people, I thought that it would be interesting to gather some information about what makes a good or a bad scientist. To this end, I designed a short questionnaire with eight questions. There was no right or wrong, nor even a preferred answer. Those were just questions to help me know the candidates better.

The first question was “What is the most important quality of a scientist?” I had no particular expectation. Actually, I did not even know my own answer to this question. As it turned out, most candidates answered that it was either creativity or persistence.

If you have been in science for even a short while, you know why this makes sense. We have complicated problems to solve, so creativity and persistence are important. Yet, I was not convinced that a good scientist is someone who is either very creative or very persistent. The reason is that neither of these qualities defines a scientist. Artists, politicians, business people, social workers and pretty much everyone else greatly benefits from being creative or persistent.

Having spent more time with scientists, I came to find the answer to my own question: the most important quality of a scientist is to be tolerant to cognitive dissonance.

What is cognitive dissonance?

The term is sometimes used in the popular language, but cognitive dissonance theory is a proper subfield of psychology. It posits that our brain spends a considerable amount of resources to maintain a coherent view of our world. Since this view is sometimes far from reality, our brain needs to patch things up. What is interesting is that we are mostly unaware of it.

Cognitive dissonance theory was born in the middle of the twentieth century from the study of an earthquake that took place in India. People who felt the earthquake but did not experience any harm or physical destruction were not relieved at all. Instead, they entered a deep form of pessimism and feared disasters to come. Pessimism seemed to mitigate the mismatch between the experienced fear and the lack of reasons to be afraid.

Cognitive dissonance can affect all our representations, and more particularly the representation of self. To reduce the dissonance, the brain will typically use strategies of neglect, post-rationalization or behavior adjustment, a little like we do on a normal day: First pretend you did not notice the problem. If that fails, find an excuse for not addressing it. And if that also fails... make the problem go away.

Among others, cognitive dissonance theory explains why people do not always respond to the feedback they receive. If your boss yells at you, the “not noticing” strategy is out, but post-rationalization is still in the game, especially if you believe that the shouting was not deserved. For instance, you may decide that “he was just in a bad mood”. But it would be harder to trivialize a comment such as “you used to work better”, because that comment is consistent with your high opinion of yourself. As a consequence, you are more likely to act on this feedback because it is less dissonant and because it leaves fewer options for neglect or post-rationalization.

Among others, cognitive dissonance theory explains why people do not always respond to the feedback they receive. If your boss yells at you, the “not noticing” strategy is out, but post-rationalization is still in the game, especially if you believe that the shouting was not deserved. For instance, you may decide that “he was just in a bad mood”. But it would be harder to trivialize a comment such as “you used to work better”, because that comment is consistent with your high opinion of yourself. As a consequence, you are more likely to act on this feedback because it is less dissonant and because it leaves fewer options for neglect or post-rationalization.

Cognitive dissonance in science

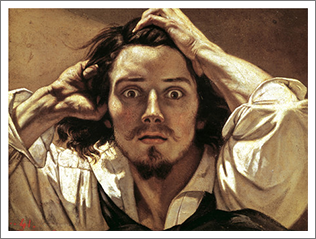

But let us return to the original question: what does this have to do with good science? Research questions are a very thorny intellectual issue. Contrary to a popular belief, scientists spend most of their time in a state of great mental confusion; they just prefer to speak of the eureka moment than the long years of confusion that led to that moment. When I say tolerant to cognitive dissonance, what I really mean is tolerant to a state of mental confusion.

Wait, am I saying that scientists should develop a state of great mental confusion? Yes! Or more accurately, that they should be relatively comfortable in this mental state because this is the way science feels. It is the mark of a poor scientist to leave this state because of discomfort instead of the absolute certainty that the problem was solved.

Thomas Kuhn in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions mentions an interesting experiment in cognitive psychology: test subjects are shown playing cards for a very brief amount of time and they have to say whether they notice anything particular. In some cards, the hearts were painted in black, but the test subjects do not notice it until a few cards of this type were shown. Strikingly, once they have spotted the anomaly for the first time, they barely miss it anymore.

Kuhn makes a parallel between this experiment and paradigm shifts: First, counter-examples accumulate but scientists do not even report them; they just treat them as outliers or measurement errors. At some point someone notices that they are too frequent to be ignored but the community does not pay attention. Finally, the community accepts that there is evidence against the current theory, and a new paradigm is chosen to replace the old one. In this regard, our capacity to integrate cognitive dissonance is the rate-limiting step of scientific progress.

Concluding remarks

Is this really a quality in the sense that one can be trained to notice and act on dissonance? I suppose that part of it is unconscious and cannot be changed. This is a good thing because most exceptions are uninteresting and they are just better ignored. But I believe that good discipline in the laboratory does bring a better sense that something is not quite right when something is indeed not quite right.

And what about you? What do you think is the most important quality of a scientist?

References and further reading

The review Dealing with dissonance: A review of cognitive dissonance reduction by April McGrath is a good introduction to the subject (behind paywall unofortunately), and the review article Optimal Conditions for Effective Feedback offers interesting connections between cognitive dissonance and effective feedback.

Uri Alon makes a nice point about the value of confusion in research in a article called How To Choose a Good Scientific Problem. He calls scientific this particular state of mind “the cloud”.

« Previous Post | Next Post »

blog comments powered by Disqus